Photo by: Shon Cobbs

I couldn’t listen to Cigarettes After Sex in my previous life. It wasn’t that I didn’t like the band. Their name is so cool, not just because of the provocative subject matter, but also because of its tonal accuracy: their sound evokes the blissful situation it describes. They’re not capturing the wholesome sense of relaxation found in nature, during a yoga retreat, or after a brisk run. They sound like the buzz of smoking a cigarette after bedding someone who bewitched you. It’s the gentle comforting of someone talking you down from a bad drug trip. It’s the complicated but yearned-for confession of feelings from a casual sexual encounter.

But each time I was sucked into Cigarettes After Sex, their sweet, slow morphine drip left me in withdrawal. Empty. Hollow.

I got a divorce, a thrilling new job, a new love, and quite honestly, a totally new life in a dizzying quick minute. After a stressful day, my modern-day boyfriend sat me on his couch with a glass of wine, played Cigarettes After Sex, and made me dinner. It was ecstasy. I felt full, I fell back in love with the band. I realized that the reason I couldn’t handle them previously was because they shone a spotlight on an emptiness in my life: I didn’t know that kind of romance or tenderness. I wanted it. In fact, my inability to handle Cigarettes After Sex at that time could be added to that list of quiet but obvious markers that I wasn’t happy with my life.

Coming full circle, I found myself reviewing the band’s Mission Ballroom show with my current boyfriend–me writing, him photographing. One thing we hadn’t anticipated: this dreamy little slowcore band had become unadulterated rockstars. Two sold-out nights at Mission Ballroom to the shrill screams of a 16+ crowd, mostly girls. Sometimes it feels humbling to be a 40 year old woman who suddenly realizes she shares the tastes of gobs of screaming teens. As we waited for the show to start, I thought about whether I’d like Cigarettes After Sex as an adolescent.

As a punk girl, I was typically turned off by anything sensual, because it felt pandering and untrustworthy, like they were trying to get into the world’s proverbial pants. Cigarettes After Sex feels like it’s written from a place of already being in your pants, detailing the complicated emotions that ensue after. I think that’s why it feels right to me. And just like I loved listening to the Cure, I think I would’ve adored Cigarettes’ dark romanticism.

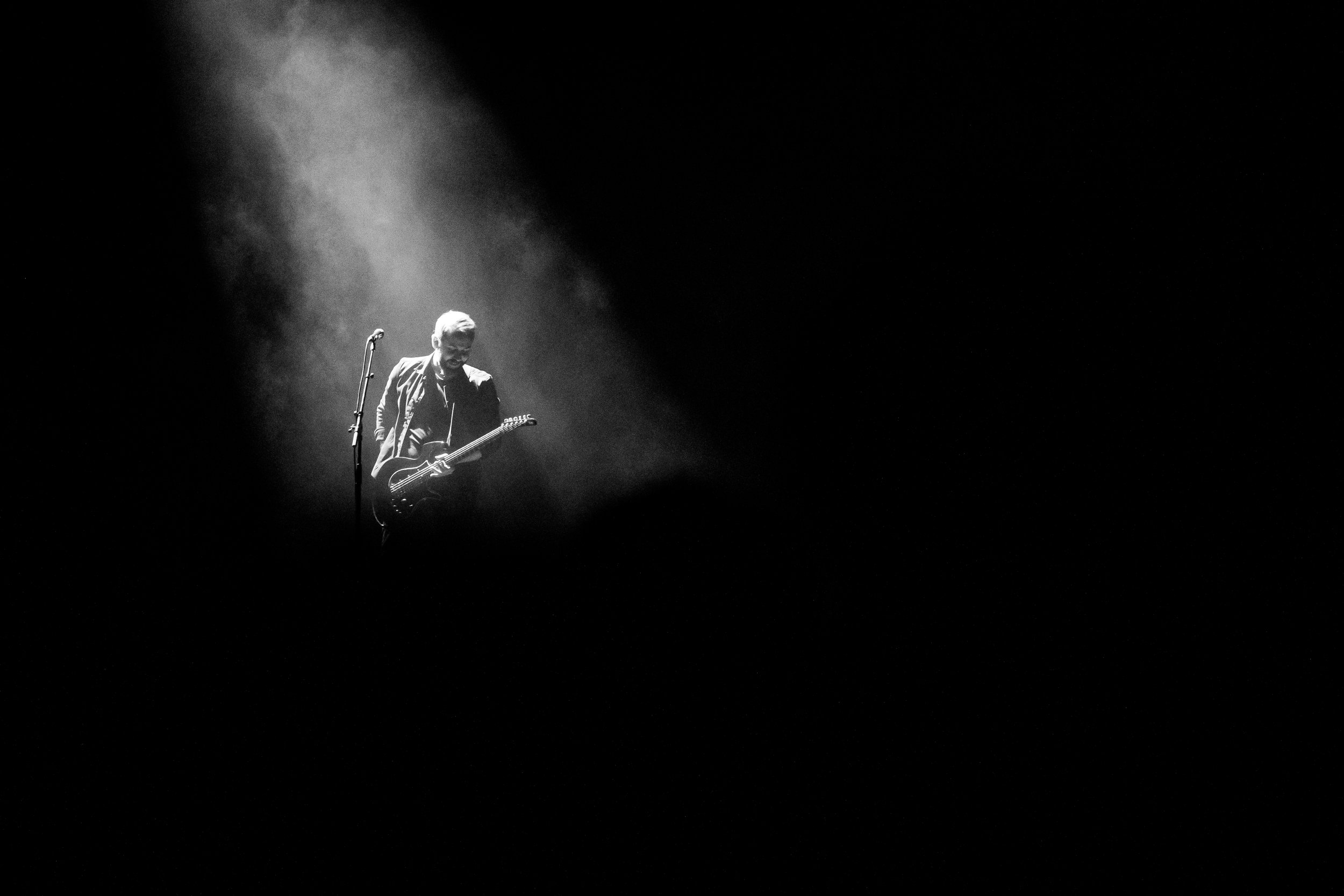

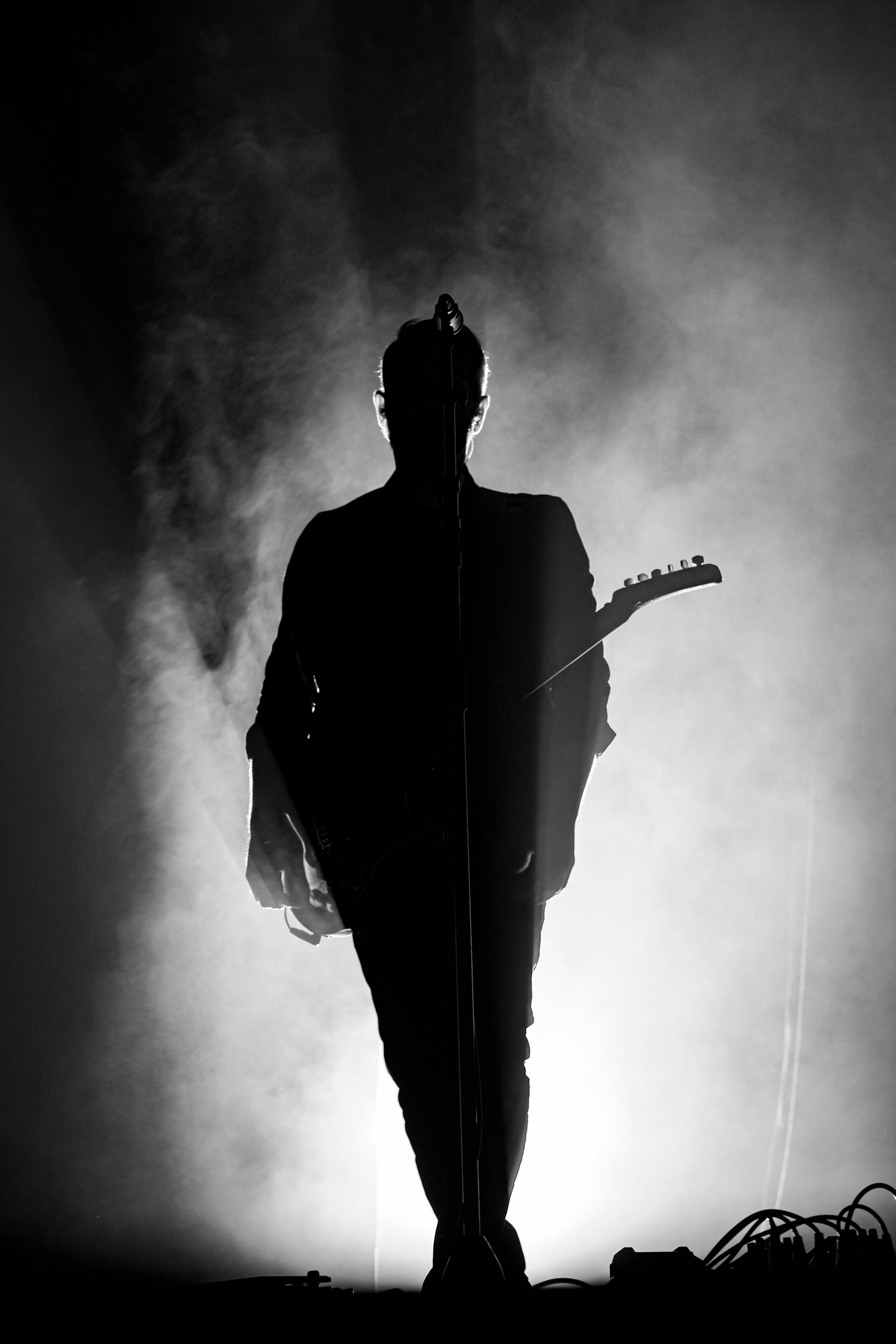

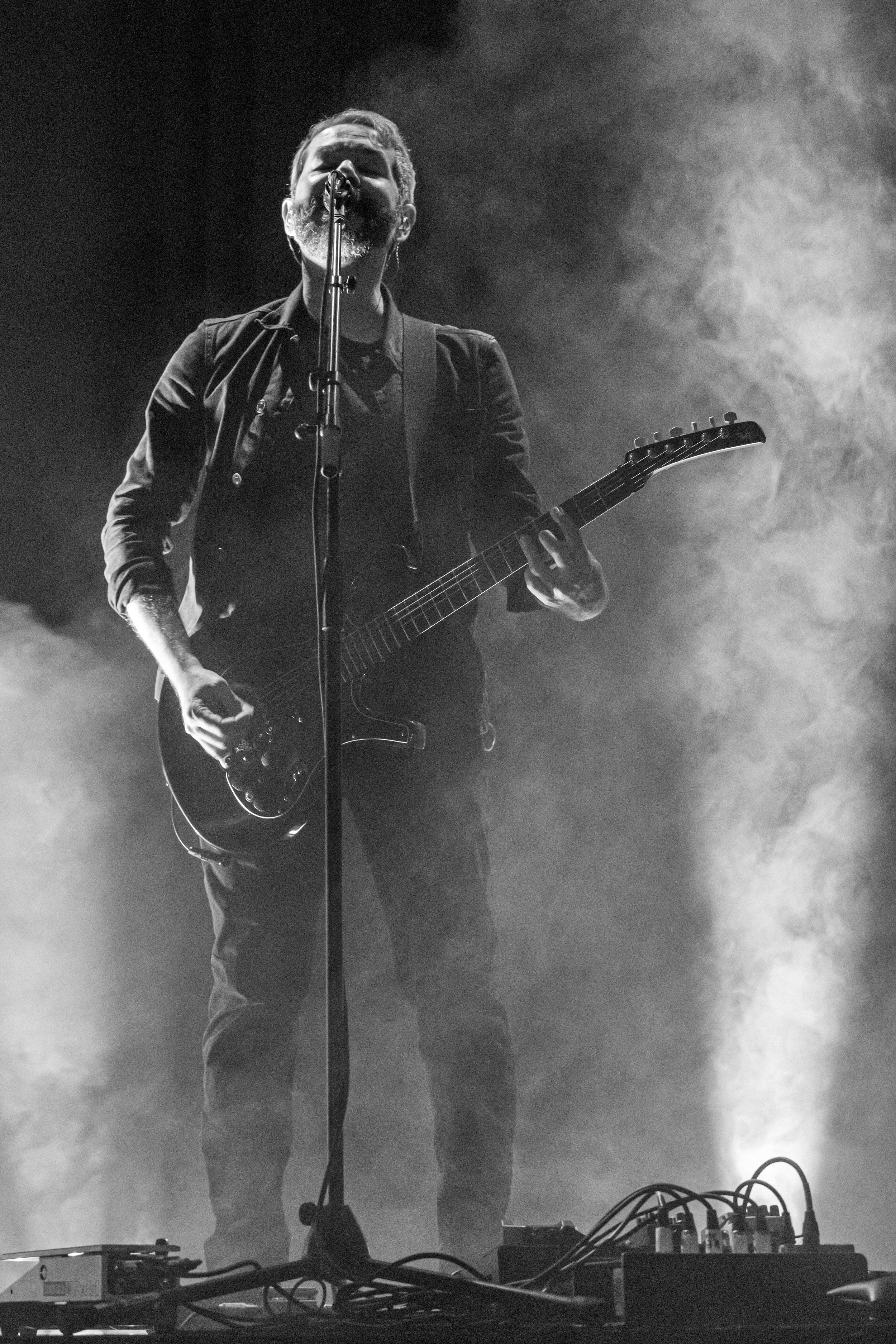

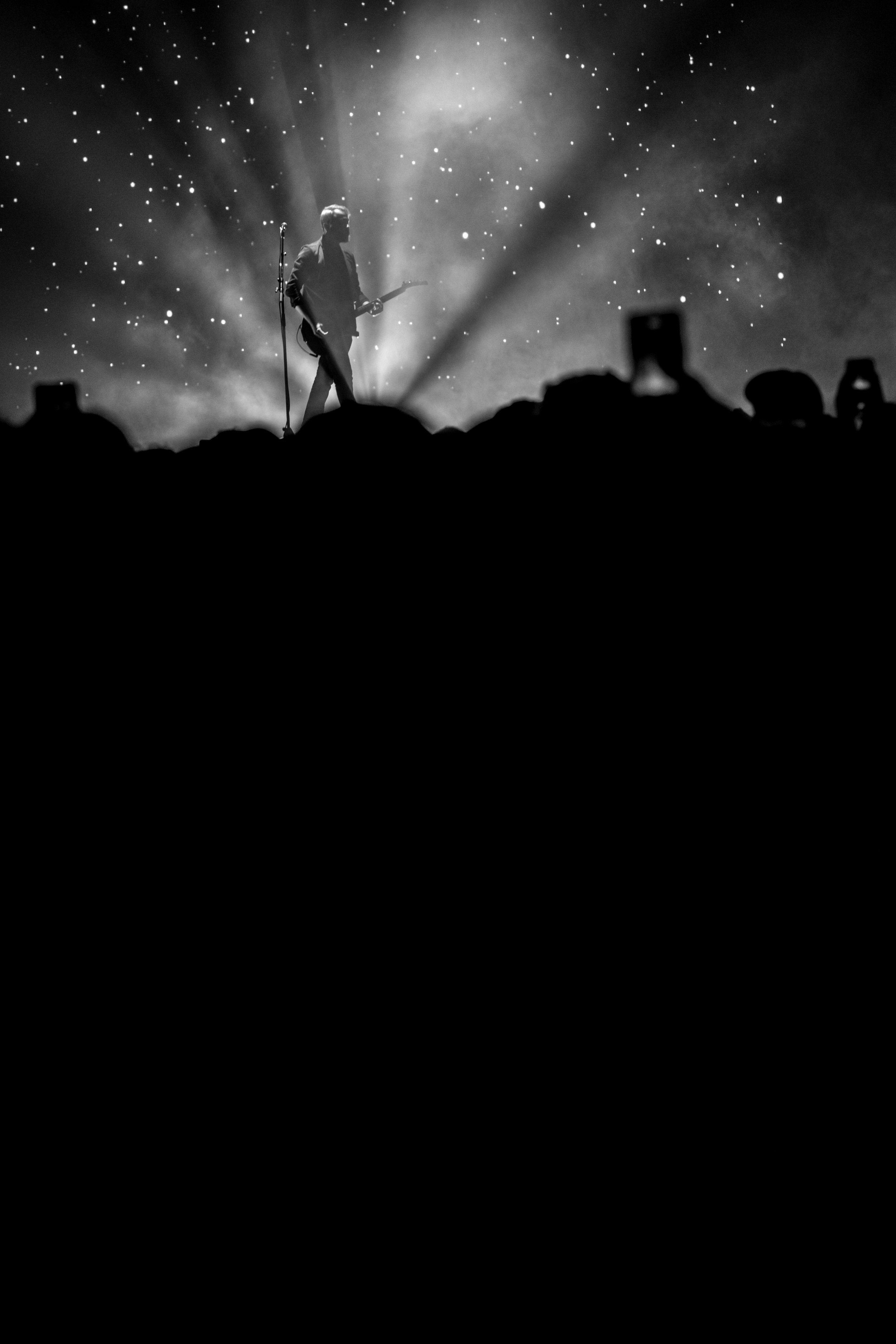

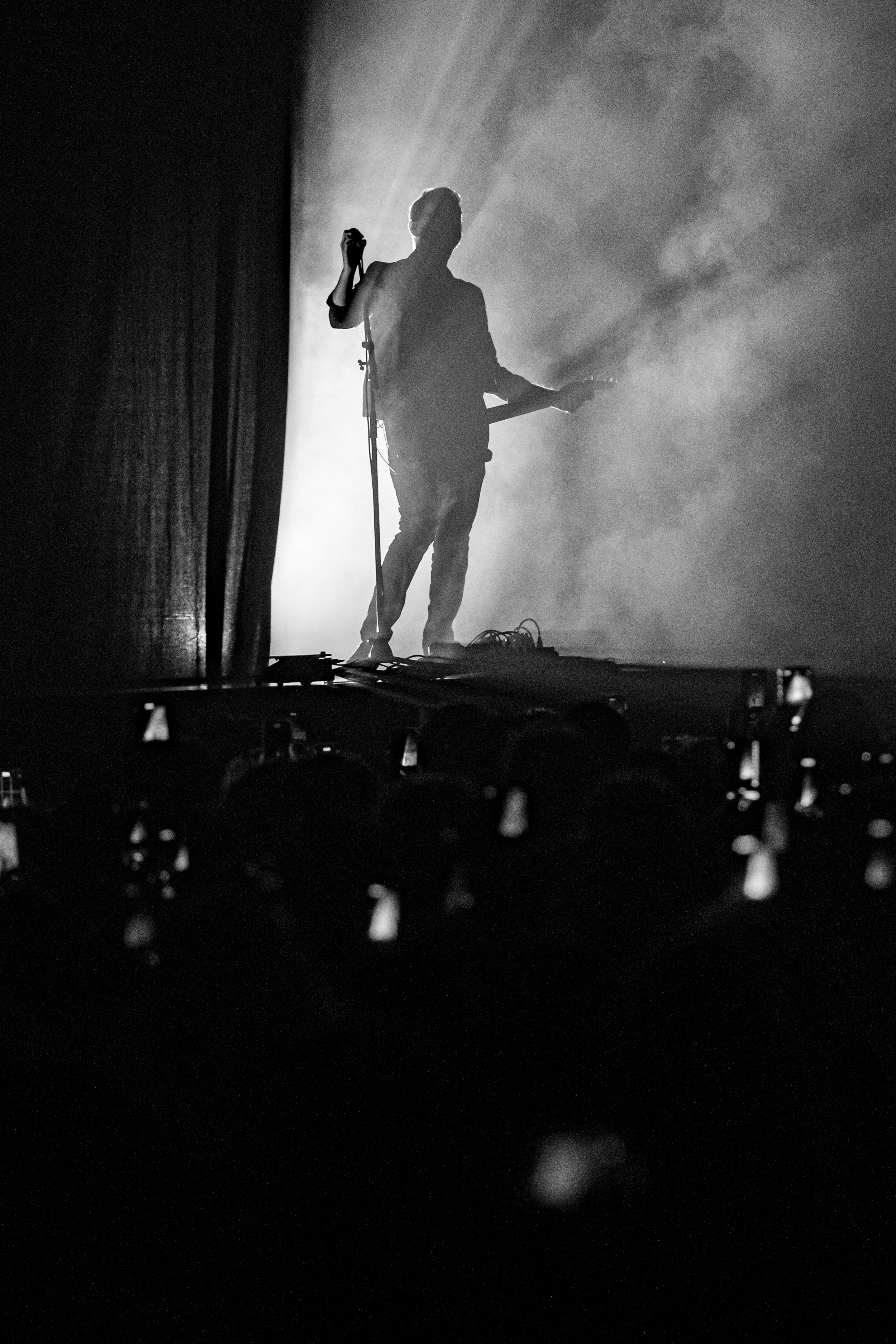

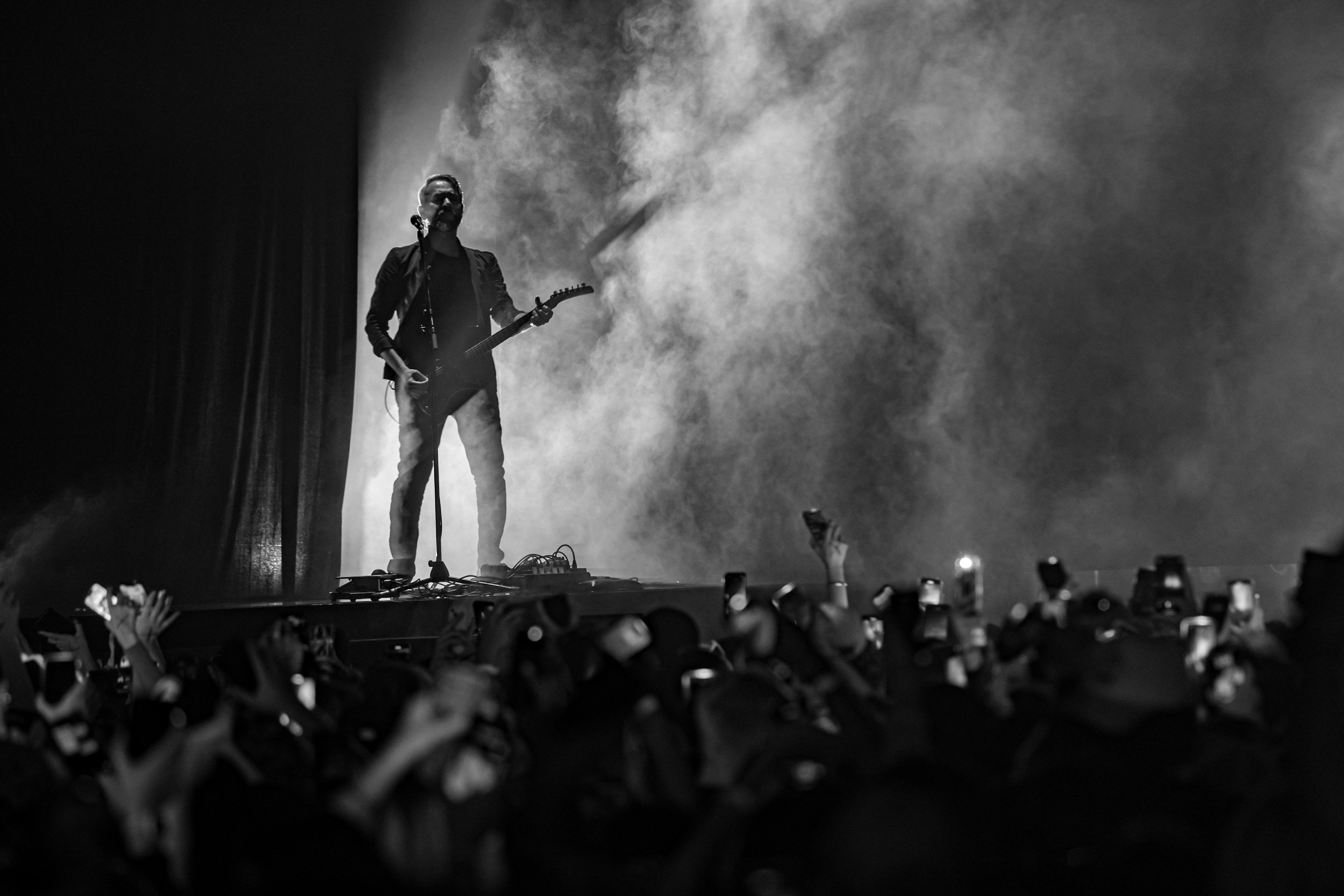

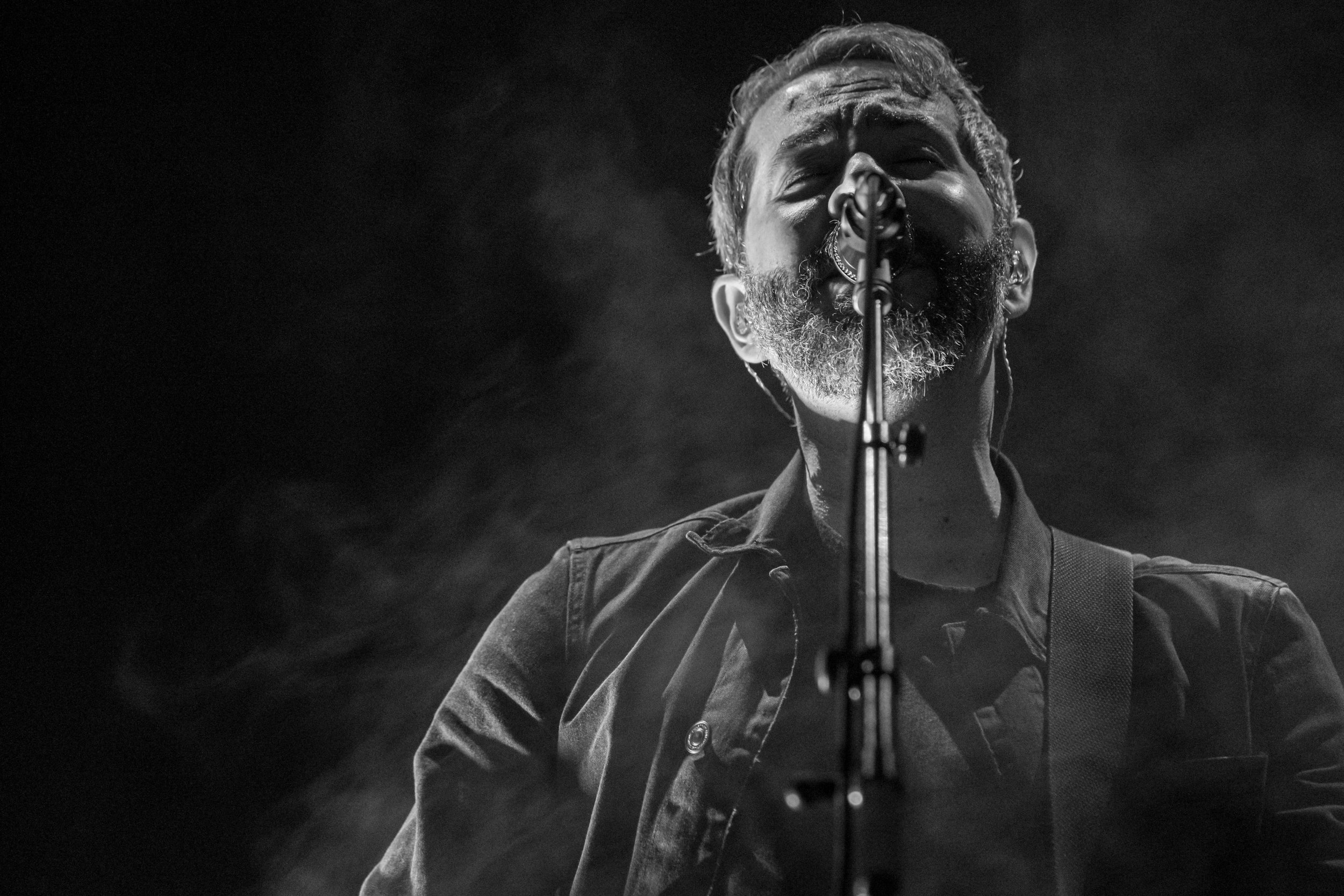

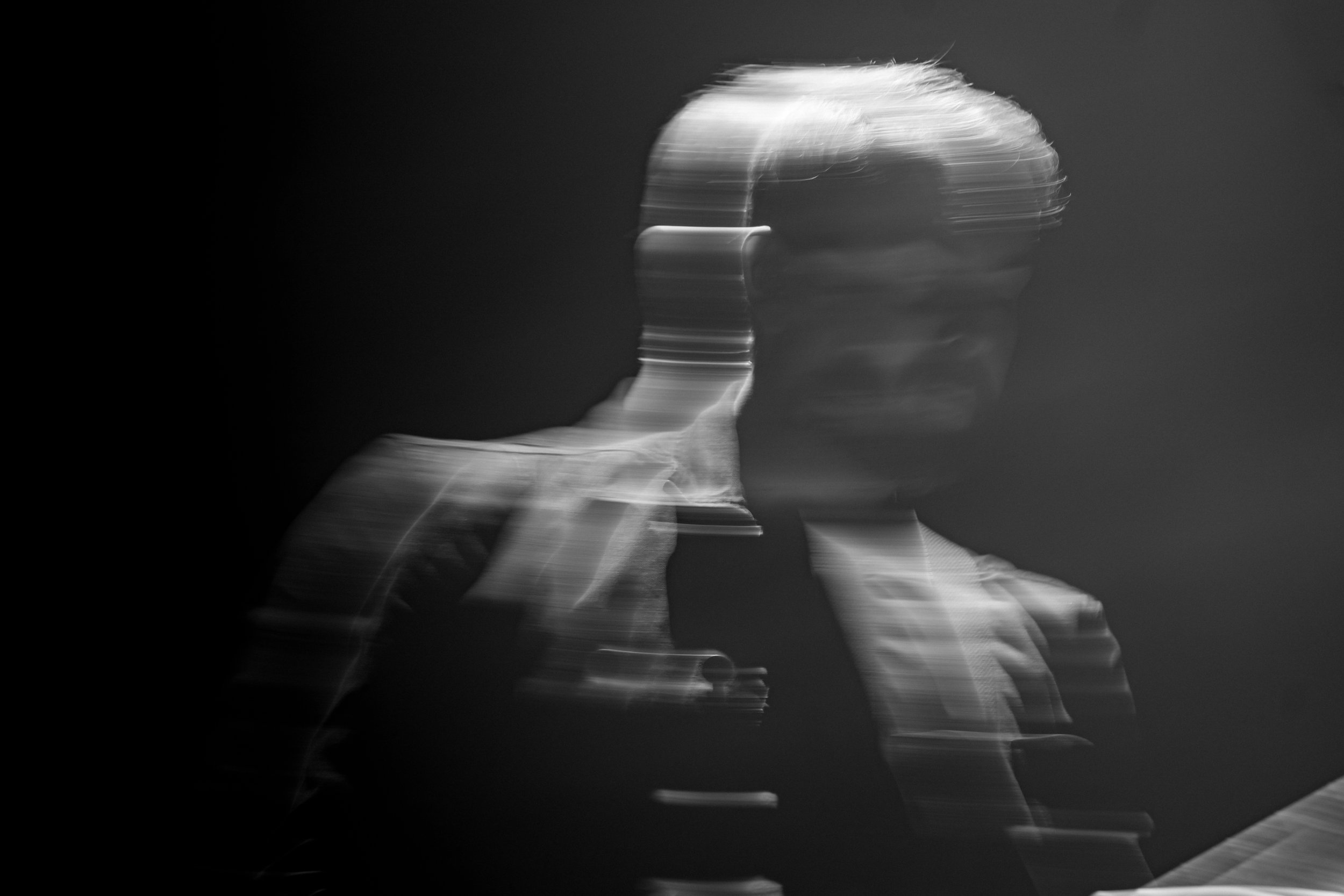

The stage was pitch dark, classical music announcing the band’s entry. They stepped out of the darkness into the crisp spotlight and churned smoke to piercing screams across the theater. For being supernaturally romantic, the band is composed of the most regular looking dudes that you’d never guess to be rockstars if you spotted them at a King Sooper’s. But they have impeccable style that transcends their visuals into the unattainable rock gods they’ve become: a stark black and white lightscape, hair fluttering in the wind, glittering spotlight and smoke. Black and white projections of iconography flashed behind them: a rose, a match burning, moonlight cascades, lightning flashing.

As lead singer Greg Gonzalez purred through the first two songs, something struck me. My ten-year-old daughter was texting me about her first day of school, and I texted her back with videos of the band and my face, surrounded by other young girls, telling her how much I wish she could be there with me. If it wasn’t already embarrassing enough being the old person at the young-person concert, like an uncontainable secret, tears started spilling down my cheeks, grossly unstoppable. There was something about this music in person, so evocative and tender, and the love that I have for my daughter, which is the greatest love of all time, mixing together to create an embarrassing soup of emotion. At least I might get points for being the biggest fan here. My boyfriend was in the photo pit, capturing incredible photos no doubt, running through the crowd to get different vantage points, and I was almost glad he wasn’t there or I’d cry harder. They sang crowd favorites such as “Apocalypse,” “K.,” and “Nothing’s Gonna Hurt You Baby,” sounding remarkably as they do in recordings. During “I’m a Firefighter,” the crowd was alight with cell phone lights, Mission Ballroom glowing eerily as if by candlelight.

A fanbase doesn’t just tell you about a band; it tells you about the world surrounding the band. In the ‘90s, Rage Against the Machine, despite being politically radical and progressive, attracted cis white meatheads. These entitled young men needed a meaning, something important to ignite their passions–instead, they knocked over speakers and set fires to music festivals. Today, life is really difficult for young people. They’ve experienced actual trauma. Fresh from a global pandemic, they’re launching anew into a hellscape of school shootings, suicide, criminal Presidents, and Tinder bois who think women lose value after each sexual encounter. Young people today need dreaminess. They need sensuality. They need tenderness. They need nuance.

After I managed to stop the embarrassing fluid from coming out of my eyes, I started to feel empty again, alone watching Cigarettes After Sex comforting this crowd with tales of dying relationships, situationships, true love, and everything in between. Then, my boyfriend Shon found me and kissed me. Making out with someone to a soundtrack of Cigarettes After Sex melts the world around you.

-Erin Barnes

Photos by: Shon Cobbs